All text and photos by Lee Weldon copyright 2011

The Western Maryland Railway, in its heyday was one of the most efficient, best run Class 1 railroad in the east, and possibly in the nation. Starting out as a regional grainger bringing crops to market from Westminster to Owings Mills before the Civil War, the WM grew to span from the Port of Baltimore to the Allegheny Mountains of Pennsylvania, and the coal fields deep in West Virginia around the turn of the last century.

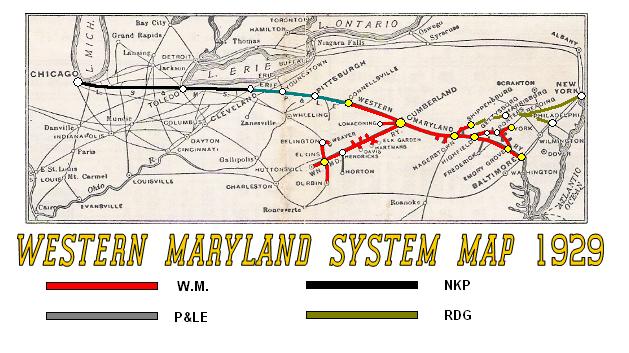

By the end of World War II, the Western Maryland was thriving on a steady diet of coal, which was moved east to the steel centers of Allentown and Baltimore, and west to the furnaces of Pittsburgh. The railway also became an important link in the "Alphabet Route," which was made up of smaller regional Class 1 railroads who coordinated their schedules to compete effectively with the major trunk lines, the Pennsylvania, B&O and New York Central. The WM's partners included the Nickel Plate, the Pittsburgh and West Virginia, and the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie to the west, and the Reading Co. and Central of New Jersey to the east. The jumble of reporting marks that would appear on the freight bill gave rise to the name "Alphabet Route."

The Western Maryland was a key player in maintaining the tight schedules of the Alpha Jets, as the fast thru freights came to be known. Their job was to move the trains over the mountains between the manufacturing centers of the midwest to the markets of the northeast, and do it faster and more efficiently than the single line hauls made by their powerful competition.

The thru freight traffic moved primarily between Connellsville and Lurgan, where the Reading connection was located. The coal would move from Elkins to Knobmount Yard near Cumberland, where it was sorted, weighed and marshalled into trains bound for the steel centers or to Port Covington in Baltimore for export.

Passenger service played a minor role in the business of the WM. When the system reached its peak mileage in the early years of the 1900's, the railroad offered thru express service to Chicago in direct competition with the B&O. This only lasted a few years, though, and service was curtailed to local trains between the WM's terminals, and seasonal excursions to its resort in PenMar east of Hagerstown. This lasted into the 1950's, when the WM's mail contracts expired, and the revenue generated no longer covered the cost of operating.

Steam also disappeared from the Western Maryland during the 1950's. Despite the fact that it made a healthy living moving coal, it was diesel fuel that took over all the road and local work by 1954. By 1955 all the steam was gone from the property, including the powerful 4-8-4 Potomacs and gigantic 1200 series Challengers, which were all under 10 years old when they met the scrapper's torch. The once thriving steam shops at Hagerstown were converted to the servicing of diesels, which kept them busy for another 25 years.

But on the WM, efficiency was the goal, and diesels required less maintenance, less manpower, and less time to get between interchange points. Through the 1950's and early '60's, the railroad cemented its reputation as "The Fast Freight Line." But the merger talks of that era began to reveal the writing on the wall. As part of the negotiations to approve the ill-fated Penn Central merger, the Norfolk and Western absorbed the Nickel Plate and the P&WV, the western partners in the Alphabet Route. N&W became a solid partner in maintaining the tight schedules, and there were, for a time, rumors that the WM would become a part of the N&W system.

But it was not to be. A large stake of the Western Maryland's stock was owned by its rival, the B&O, held in a blind trust managed by Wall Street bankers, and had been since the 1920's. While the B&O wasn't permitted to vote its stock for much of that time, by 1966 the ICC had lifted that restriction following its merger with the Chesapeake and Ohio, which also owned a piece of the WM. In 1964, the first evidence of outside influence appeared when the WM's fleet of SD-35's were delivered bearing the C&O/B&O's number series. In 1966-67, the five GP-35's were renumbered from 501-506 to 3576-3580 reflecting the new system. All locomotive purchases from that time until the Chessie inclusion in 1973 may have worn Western Maryland colors, but they all came with B&O numbers. A group of GP-40-2's were delivered in 1974 were the first new WM diesels delivered in full Chessie regalia.

In 1973, the Chessie System, a holding company formed to own the WM as well as the C&O/B&O, took control. The WM's senior staff, the men who led the railroad successfully while most of the railroads around them struggled under ICC regulation, were gone, replaced by Chessie functionaries. While the terms of the merger required that the WM maintain its own sales force and train schedules, the management in Cleveland didn't make life easy.

Chessie's operations people determined that the parallel routes of the B&O and Western Maryland between Cherry Run and Connellsville represented a costly duplication of facilities, and filed to abandon the WM west of Hancock. In the summer of 1975, the rails were cut, and service halted over much of the old "Fast Freight Line" as WM trains were diverted to the B&O. B&O dispatchers weren't as concerned about maintaining the level of service the WM's customers were used to, and business started drying up.

At the same time, much of the coal that had been the life blood of the Thomas Subdivision and the export facilities at Port Covington began being diverted to the C&O in West Virginia, and to the B&O's Curtis Bay facilities in Baltimore.

No longer needed on home rails, the once proud Western Maryland fleet became threadbare, wandering the Chessie System from Saint Louis to Cleveland to Richmond. Eventually the handsome black and gold speedlettering and the bold red, white and black "Circus" scheme gave way to the garish Chessie colors and sporadic maintenance.

By 1983, the corporate life of the Western Maryland Railway came to an end. The largely paper company became a part of the C&O, and the operations were taken over completely by the B&O. Then, almost in the same breath, those two long-lived roads lost their identity as they were swallowed whole by CSX Transportation.

Today, only the east end of the railroad survives in Class 1 service, with the Tidewater Sub from Baltimore to Emory Grove, and the Dutch Line from Emory Grove through Hanover, PA to Hagerstown, and the old main from Hagerstown to Cherry Run being operated still by CSX. In Baltimore, the once-bustling terminal at Hillen Street is now a parking lot, and Port Covington became the site of an industrial park, and a Walmart Super Center. The Hagerstown yard has been reduced to a local switching yard, and the old roundhouse and shops were razed in 2000 despite feverish efforts by the Hagerstown Roundhouse Museum, Inc. to save it. The old East Sub through Westminster was revived in the late '80's by the Maryland Midland, which continues to provide rail service to much of Carroll and Frederick counties. In 2007, the Maryland Midland itself was absorbed into the Genessee and Wyoming group, which owns short line and industrial switching railroads around the world, although a 49% stake owned by the parent of Lehigh Cement provides for a promising future despite out of town management. Lehigh's largest cement plant in the western hemisphere is served by the Maryland Midland at Union Bridge.

My first experience with the WM came two years after much of its line had been removed. My father was a traffic manager who was frequently called upon by railroad sales reps. At his annual Christmas Party, Dad would invite these fellows to our house, and on occasion they would invite him and his family to special outings. In the summer of 1977, we were invited to ride the Chessie Steam Special, an excursion hosted by Chessie that would depart from Camden Station in Baltimore and carry us to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia and back.

While riding the train, I sat with Dick Costello, the Baltimore District Sales Manager for the WM since the late 1950's, and one of my dad's best friends. While other kids were receiving Chessie patches from the conductors, Dick pressed a black and gold patch into my hand, bearing the classic WM in speedlettering.

"Here kid, this was a REAL railroad," he said. He was obviously bitter about the transition that had been foisted upon him and the other WM executives by Chessie. He still had a few years to work before his retirement, and he knew it would be a struggle to keep his head while all the work he had done over 25 years was unravelled in a matter of months. Years later I interviewed him as part of the oral history project undertaken by the Western Maryland Railway Historical Society, and he related to me some of the stories that still left him shaking his head. They are detailed in the Society's book Working on the Western Maryland Railway edited by Wes Morganstern. In 2007 Dick passed away. My father's been gone since 2005. I'll miss seeing him at the holidays every year, but I can assure you, I still have that black and gold patch.

It was a great company that did a great business in a beautiful part of the country. I'm proud to have gotten to know people like Dick Costello, as well as the many members of the WMRHS. It's those relationships and those memories that inspired me to research and build this layout.

The spirit of the Western Maryland continues to echo, though, whether its through the conversion of its right of way to use as a hiking and biking trail, in hundreds or even thousands of model railroads, or in the smoke and steam of a tourist railroad that still plies its rails through the Cumberland Narrows. It's a fascinating history to learn about, and a great example of American railroading at its finest.

Lee hanging out trackside in York, PA... Photo by Ed Kapuscinski

About Lee Weldon

My father, Stew Weldon, was a Traffic Manager for Martin Marietta Chemicals, and most of his best friends were railroad sales reps. As a kid, I was constantly barraged with notepads, paper weights, tie pins and who knows what else with railroad emblems on them. Dad also liked to tinker, so there were always projects going on around the house. In retrospect, I never had a chance.

I started working in N scale when I was about 11 or 12, so I've been actively engaged in the hobby for about 30 years now. I got N scale because my brother got to work on the HO Christmas Garden with the old man, and my corner of the basement was much smaller. The good news was, when Mark's stuff came down in January, mine got to stay up because it wasn't in the way. Outside of a few lapses when we moved, I've had someplace to run my trains pretty much on a continuous basis since then.

In 2012, my life took a sharp turn for the good, and the Western Maryland Western Lines had to be sacrificed at the altar of personal growth. Much of it survives having been carted off to several basements in the Baltimore area for resurrection as parts of other layouts, and I have retained most of my collection of rolling stock and scenery components. I'm working on designing a smaller, more portable layout that better suits my lifestyle. I continue to enjoy operating on the layouts of friends.

I'm currently working for myself again as a residential designer based on Maryland's Eastern Shore. You can also continue to read my scribblings in N Scale Magazine, I've written a few articles about my layout, and a few others, and also "The N Scale Approach," a periodic commentary about the joys of modeling in 1:160.

Andy and Julie at the B&O Museum in Baltimore with WM 236.

The WM facilities at Port Covington in Baltimore, shortly before their demolition in 1989.

The WM was proud to put its name on nearly all of its bridges and overpasses.

The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad runs steam powered excursions behind 734. This 1916 Baldwin 2-8-0 was given a face lift to more closely resemble the WM Alco that originally wore that number.

This video was shot in February, 2007 at Belington, West Virginia. WM 82, an historic EMD BL-2 diesel electric, continues to be used in regular revenue service on the West Virginia Central Railroad. She stands as a testament to the Western Maryland men who maintained their fleet to such high standards.

This 1989 photo taken at Riverside in Baltimore shows what had become the "Last Western Maryland Diesel." GP40 6573 was still wearing the paint she wore when delivered new to Hagerstown back in June of 1971 as WM 3798. She would run for several more years for CSX, and was finally retired after a major mechanical failure in the early '90's. Aside from the slap-dash renumbering job, she never wore Chessie or CSX colors through her entire career. I believe she was ultimately brought back to life by a rebuilder, and is back in service on a short line or for a leasing company.

WM 67 pulls an excursion for the West Virginia Central. The train runs out of the newly restored Elkins depot. Photo by Skip Barber, used by permission.

Salisbury Viaduct is almost 2,000 feet long, and carried the Western Maryland's Connellsville Sub across the Casselman River valley. This was one of the many engineering marvels that were part of the "New Line" built in the early part of the 20th Century.

Looking east down the WMRHS platform. The museum is open Sundays from 1-4 p.m., and at other special times as advertised.

The Maryland Midland operates the line through Union Bridge now. One of their fresh looking GP-39's pauses in front of the MM's attractive headquarters. Sadly, the Genessee and Western took over the MMID, and this handsome paint scheme has been replaced with their awful orange paint.

Another great resource for WM heritage is the Hagerstown Roundhouse Museum, located in the former engineering offices of the WM. Their goal was to preserve the roundhouse and backshops as a working steam preservation shop and museum, but this goal was thwarted when "Chessie the Knife" tore everything down in the summer of 2000. The museum soldiers on, however, featuring a scale model of the complex, and numerous artifacts of the WM's chief terminal.

You can also still see CSX trains traversing some of the WM route in the Potomac River valley. This bridge stands at McCoy's Ferry, not far from Ft. Frederick State Park. It's part of the active line between Hagerstown and Cherry Run, where it joins the former B&O main line.

I hope you enjoy this site as much as I've enjoyed cobbling it together.

Ain't nuttin' bettah! Y'all come back now, hear?